Off-Note: Lessons from a Third Annual Reading of "A Christmas Carol"

Nowhere local this time folks – but when's the last time you read some Dickens?

This is not quite the same as our normal programming, and I know I am in arrears in sending out a new Local Note, so I have to doubly apologize. But in case you wanted to hear my pundit’s voice on at least some kind of topic as we turn into 2025, here’s a – certainly unsolicited – musing on Charles Dickens. May the new year bring new, and ever more local, adventures to us all.

For the past couple of years, I've tried to read Charles Dickens' "A Christmas Carol" at Christmastime. Previously, I reflected on these readings here.

I say try because this year I half-failed: I had my most unconventional Christmas so far, spent at my house in Los Angeles with my fiancée but away from either of our families – a surprising late wrist injury (Stevie Wonder concert, ice skating) being the blocker to either of the 1000mi+ trips that visiting would have required. We got a tree up and trimmed but late, and lights got on top of our roof not before the evening of the 23rd. On Christmas morning, we opened gifts with each other and our dog Murphy, but having little of either shrieking toddler or siblings looking for something to do, we instead relaxed and watched the Bob Dylan movie in the evening before going to get sushi.

This is not to say it was anything other than sweet or enjoyable to spend a long holiday with my wife-to-be in our settled city – I was quite at ease – but Christmas, as Dickens explains, is enriched by being close to family, even if that is not necessarily a requirement for getting into the feeling of the season. Despite it all, I didn't want to throw away a nice new tradition, and so on January 5th, I cracked open "Carol" and began again.

This time what impressed itself more on me was neither the language of the "Spanish onions" nor the asides to utilitarianism nor the commentary on nineteenth-century carceral organization in the Home Counties, but rather how Dickens talks about Scrooge and his sadness. It really is the case that you have to "begin with" the fact that Marley was dead, even if it was some seven years prior to the start of the novel. It has clearly not been time enough for Scrooge to move on – he lives in Marley's old house, has not erased Marley's name from the shingle of their business, has visions of Marley's face in his furniture, and indeed even lets people call him Marley: "Sometimes people new to the business called Scrooge Scrooge, and sometimes Marley, but he answered to both names. It was all the same to him."

There's not a lot of evidence that prior to Marley's death Scrooge was not "a squeezing, wrenching, grasping, scraping, clutching, covetous old sinner!" But we should certainly interpret his shrinking from the world in terms of the fact that he is a man alone from someone with whom he shared a life. In fact, everyone who was good to Scrooge in his life seems to be dead by the time of the Christmas portrayed in the novel: we can consider Old Fezziwig, who Scrooge and the Ghost of Christmas Past visit, and Scrooge's cry "in great excitement" that "it's Fezziwig alive again!" Or we can consider Scrooge's sister, who rescues him from the privation of his school days. As the Ghost tells us, "she died a woman".

There are others in Scrooge's life we could consider. There are the strangers in the streets of London, as well characterized as any of the other major characters in the novel, and yet we know that they all avoid him: "Nobody ever stopped him in the street to say [how are you]...no beggars implored him to bestow a trifle...". There are the other businessmen he deals with from time to time, but Dickens emphasizes the distance between Scrooge and his counterparts – although Scrooge "made a point always of standing well in their esteem," this was "strictly in a business point of view". At the end, they cannot even be bothered to attend his funeral. There's his washing lady, but she is forecast to steal his curtains right off the rods while his cold body lies dead in the bedroom.

There's actually quite a bit of discussion about the role of purely economic relationships in Scrooge's London. Adam Smith's oft-quoted quip on self-interest, "It is not from the benevolence of the butcher, the brewer, or the baker, that we expect our dinner, but from their regard to their own interest," is an important jumping-off point. For although we get the magical depictions in Stave 2 of the poulterers and fruiterers and grocers, with scenes so alluring as to "make the coldest lookers-on feel faint and subsequently bilious", while shoppers crowd about "in the best humor possible," it is not out of a sense of communal charity that motivates the feeling. In what is maybe the silliest part of the novel, Dickens in fact tries to provide an explanation for this mood: as people arrive at the baker's with their dinners, the Spirit "sprinkled incense on their dinners from his torch...a very uncommon kind of torch, for once or twice when there were angry words between some dinner-carriers who had jostled each other, he shed a few drops of water on them from it, and their good humor was restored directly."

The idea of a godly intervention from the half-naked Spirit of Christmas Present (or one of his 1,800 siblings) generating these heights of feeling seeming farfetched (why does his torch generate incense? why drops of water?), I instead think the novel shelters behind the Spirit a more important notion – that these scenes emerge from the nexus of a pure and familial love and the splendor of nineteenth-century London commerce. For we know the empire at this time could summon anything to London: "Spanish onions" or "sticks of cinnamon so long and white" or "French plums [blushing] in modest tartness" or "Norfolk biffins, squat and swarthy". Abundance and capitalism and empire are not sufficient to generate the Christmas spirit, but once set in combination with the mothers and fathers speeding back to set the pudding on the copper, you get the emergent, unconscious biliousness that Dickens' narrator prizes.

Yet a critical part of "Carol"'s magic is in its careful distinguishing between different types of relationships, including its identification of where pure economic interest can cross the line into personal affection. The narrator holds out the relationship between master and apprentice as meriting special attention – Old Fezziwig is a paragon of communal conviviality in his exhortation to his boys to slough off their work and start the fiddle going: "No more work to-night. Christmas Eve, Dick. Christmas, Ebenezer! Let's have the shutters up"! Scrooge's reflection notes that the master's power "lies in words and looks; in things so slight and insignificant that it is impossible to add and count 'em up...the happiness he gives, is quite as great as if it cost a fortune." And of course, upon returning from his sojourn with the Spirits, and spending Christmas with his nephew, Scrooge's ultimate act of reinvention is to bring Bob Cratchit in closer: "He did it all, and infinitely more; and to Tiny Tim, who did not die, he was a second father."

The cold Scrooge is a caricature of the self-interested businessman, ensconced in a web of social relations as part of his economic place in the world, and yet wholly out of it, like some sort of Jesuit father of warehousing. As Scrooge's betrothed complains of his heart, "another idol has displaced me...a golden one". Scrooge is saved by reintegrating consideration for others into the neat organization of his economic life. Perhaps here Dickens belies a soft criticism of the nature of economic partnership – for as Marley had to leave Scrooge and the world behind, he left him fallow. Partnership, even if it could keep Scrooge his sanity, expires at the death of the partner. The immortality of charity and the knowing self-perpetuation of parenthood – the idea that a child can be "a spring-time in the haggard winter of his life" – are in Dickens' work the keys to happiness.

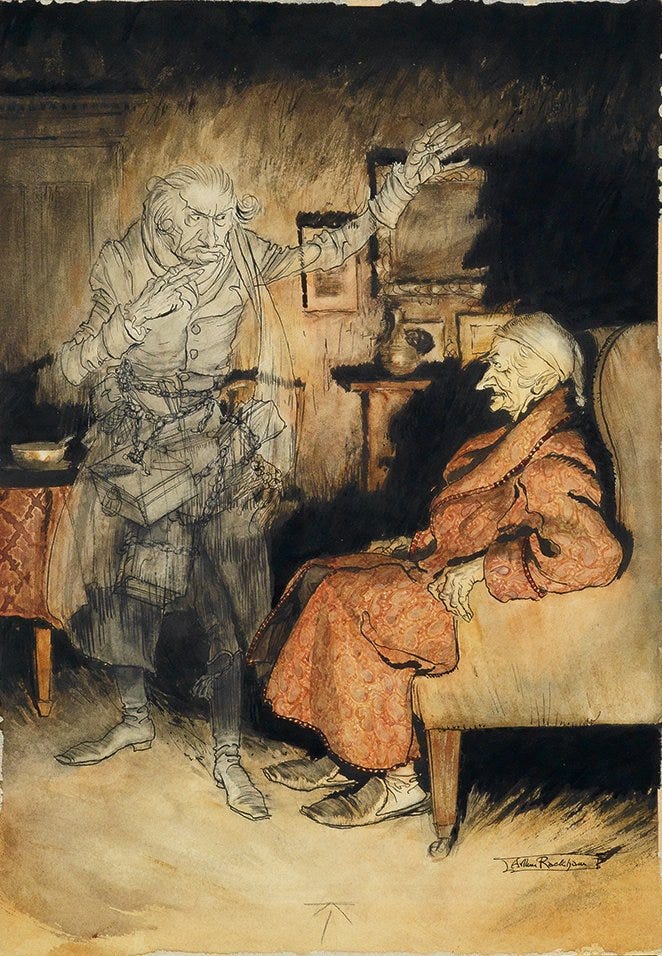

For one last piece of evidence, Scrooge’s encounter with the Ghost of Marley is the plainest sign of the novel’s morals. “Mankind was my business,” the Ghost cries, “the common welfare was my business; charity, mercy, forbearance, and benevolence, above all, were my business.”

Otherwise a few notables in "Xmas Carol" 3:

So much specificity about time in the novel: the action opens at 3pm on Xmas Eve, even if “it was quite dark already”. The Spirits come to Scrooge first “when the bell tolls One,” and then “at the same hour,” and last “when the last stroke of Twelve has ceased to vibrate”. Cratchit’s toast to Scrooge puts a pall on the party for “full five minutes”. On Boxing Day, Cratchit arrives to work “full eighteen minutes and a half” after 9am.

Each time I find a different scene confusing. This time it’s the second place visited by Scrooge and the Ghost of Christmas Yet to Come, when Scrooge’s washing lady comes to the pawnbroker with his curtains. There’s lots of people in the scene being generally up to no good, but otherwise I’m not really sure what we’re supposed to be getting out of this. Dickens must not have had any soft spot for the business of pawnbroking – the broker works in “a den of infamous resort,” in a “cesspool,” one where “the whole quarter reeked with crime, with filth, and with misery”.

There’s also a line this time I find particularly confusing: while Scrooge and the Spirit of Christmas Present watch his nephew’s party, Scrooge thinks “if he could have listened to [the music] often, years ago, he might have cultivated the kindnesses of life for his own happiness with his own hands, without resorting to the sexton’s spade that buried Jacob Marley.” Did Scrooge kill Marley?

I think Dickens’ prose styling is basically unmatched, certainly not by anyone in our century and seems tough to find people in the previous one to give him a fight. This time my favorite line was: “Gentlemen of the free-and-easy sort, who plume themselves on being acquainted with a move or two, and being usually equal to the time-of-day, express the wide range of their capacity for adventure by observing that they are good for anything from pitch-and-toss to manslaughter; between which opposite extremes, no doubt, there lies a tolerably wide and comprehensive range of subjects.” They plume themselves! Come on! The narratological asides, that’s what we’re here for – the voice!